I never would have imagined I would spend time as an ordained monastic, yet looking back I see how it was a gradual process over years of practice. When the time came, the decision to ordain felt like the most natural thing to do. [You can read the first post in this series, about the decision to ordain here.]

The Naturalness of Letting Go

When we think of “renunciation,” very few of us feel joy and enthusiasm stir in our hearts! For most, the word conjures up associations of deprivation, lack, and straining against our desires. And while renunciation does entail restraint and bearing with discomfort, it is also about so much more.

Notice instead how your heart responds to these words: simplicity, contentment, fulfillment. Or to this one: non-addiction. The associations we make with these words begin to describe the often-misunderstood terrain of renunciation, and its fruits.

From the ordinary perspective – that happiness comes from getting and having things – renunciation poses a threat to our well-being. It means, “I can’t have what I want,” which generally translates into frustration and disappointment, or worse: anger, resentment, envy. Yet for the contemplative, renunciation appears as a vehicle for fulfillment, for resting in the knowledge of what is enough.

“The rarest human experience is not bliss. It’s contentment.”

– Ajahn Sucitto

One who undertakes a thorough investigation of craving, who carefully studies the limitations of sensory experience, understands that the most enduring happiness is an openness, an inner freedom that arises through letting go. The Buddha is purported to have spoken about this very process. He recalls how before his Enlightenment he had thought:

“‘Renunciation is good. Seclusion is good.’ But my heart didn't leap up at renunciation, didn't grow confident, steadfast, or firm, seeing it as peace.” (AN.9.41)

He explained that he didn’t feel excited about the idea of giving things up because he had yet to fully understand the drawbacks of the ordinary world we live in or the benefits of letting go and living more simply. I find it striking to read these words and see how well they match my own experience: how my disillusionment with worldly pleasures, roles, and accomplishments, and my recognition of the potential rewards of voluntary simplicity, led naturally to renunciation.

“What’s an Anagarika?” The Structure of Training

I chose to undertake the Anagarika training because I wanted to broaden the depth and breadth of my Dhamma practice beyond formal meditation. In my monastic teachers, I had seen the results of dedicated practice with renunciation. I wanted to follow their example, to make my life into a training, all activities and moments a vehicle for wakefulness and care.

The Buddha’s teachings present a map, a path to do just that. The monastic tradition centers around a detailed training system created by the Buddha, maintained and elaborated by generations since, that involves a significant degree of mental, emotional, and material renunciation in service of spiritual awakening.

In the Thai Forest Tradition, the Anagarika (literally, ‘homeless one’) is the first step in this training. One is considered pre-novice, an “acolyte” or “postulant.” The core of this formal training is the eight precepts. In addition to the five ethical precepts of lay Buddhists (to refrain from killing, stealing, causing harm with sexual energy, speech, or intoxicants), one commits to the renunciate precepts of complete celibacy, not eating after mid-day, refraining from “entertainment, beautification, and adornment,” and moderation in sleep.

Consider how giving up dinner, snacks, sex, music, movies, style, and sleeping late would create certain immediate shifts in one’s life. For starters, one has a lot more time – and that’s partly the point! By choosing to live with less, one regains a great amount of time and energy. And in the monastery, those resources are used to train the mind.

Of course giving up these comforts brings certain challenges, which is also the point. Giving up the pleasures of lay life only makes sense when we understand their limitations, and what we gain in their place. When this is clear, renunciation is a choice, and we willingly agree to any discomfort it may bring.

A Fundamental Reorientation

How’s it feel to not get what we want? Generally, not so good. And so, in ordinary life we do as much as we can to keep that from happening! Lay life offers the freedom to follow desire, to pursue and hopefully attain one’s wishes. Renunciation offers the freedom to study desire, to look within the mind and understand the mechanism of craving and its release.

“Renunciation is giving up the tendency to always maximize pleasure.”

– Ajahn Viradhammo

This fundamental shift in the heart runs through the entire path of Buddhist practice. Instead of orienting around pleasure and getting what we want, we orient around Dhamma: around understanding the way things are and letting go. In this way, the whole trajectory of the path can be understood as a process of renunciation. From the practices of dana (generosity) and sila (ethics) right up to final liberation, the inner gesture of heart is the same: letting go. To give requires letting go. To maintain ethical standards we renounce the immediate satisfaction of certain drives that may cause harm.

To make this shift requires that we investigate the assumption that fulfillment comes about through grasping – through getting, having, or becoming anything (even enlightened!).

This kind of renunciation goes against the current of nearly everything we hear and see in society, in the media, and in mainstream culture. Most of the messages we receive from an early age tell us that our happiness, our success, even our self-worth depends on how much we have, on what we produce, or on how well we perform. We are bombarded by messages like this so continually that our very sense of identity gets tied up with external measures.

When we believe these messages we lose touch with our sense of inner value and begin to judge ourselves based on the externals. This is spiritual poverty: a sad state of affairs indeed. To undertake spiritual practice means to go against the force of all of this conditioning.

Learning How to Let Go

How do we know if we’re holding tightly to something? Look at what happens when it changes. We need a reference point to recognize where we’re holding on. And this is where the practices of formal renunciation (precepts, training rules, sense restraint) come in. A form gives us something to push against and notice where we’re stuck.

Anagarika training involves much more than the eight precepts and wearing white. It entails significant changes in appearance, activity, status, role, power, and even comportment – each of which has its challenges and effects.

When I ordained, I gave up a certain degree of autonomy over my time and activities. Everyone in the monastery follows the daily schedule, rising at 4:30 a.m. for morning puja, doing chores, work period, and taking the main meal of the day by 11:00 a.m. Anagarikas are in a role of service, so in addition to the daily routine I often had plenty of work to do managing the kitchen, driving monks to appointments, receiving lay guests, etc.

The monastery also functions as a hierarchy, and Anaragikas rank at the very bottom. I deferred to those who were senior to me and followed their instructions, including those younger in years or (in some cases) in practice. This gave me ample opportunity to observe how I would get hung up on being right, being in charge, or knowing the best way to do something.

Another facet of monastic training is what’s called “admonishment” (an arcane translation). This is feedback generally about how to follow the form, and occasionally on more sensitive matters of behavior or personality. While the monks aim to do this in as skillful and loving a way as possible, it took some time before I learned how to simply listen to what was offered and say thank you without arguing, explaining, or defending myself. As a white male, conditioned with a degree of entitlement around power, this training was particularly beneficial in learning humility.

The gestalt of all of these rules can seem stifling from the outside. Yet the form provided a structure that allowed me to observe and train the mind. It’s easy to be non-attached when everything is going our way. It’s when we don’t get what we want, when the mind is required to follow certain rules, that its modus operandum is revealed.

The form provided a structure that allowed me

to observe and train the mind.

I saw how blindly and compulsively I expected things to conform to my preferences (like when the lights are turned on or off in the meditation hall) and how childish the mind can get when this is challenged. I began to learn how to use the form wisely – for investigation, for cultivation of wholesome qualities, and for letting go. The overall effect was one of lightening the heart, softening my edges, and sharpening the mind.

Life in the monastery offered countless opportunities to see when and how I created unnecessary suffering. All night mediation vigils were prime territory for this. I watched the mind begin to wriggle and whine about being tired, and felt the sweet relief of letting go as I understood the futility of complaining, smiled inwardly, and settled in for a night of groggy meditation.

I recall raking leaves one cold, rainy afternoon. I didn’t see the point in raking this portion of the property and believed that I was working harder than the others. I found myself getting angry, muttering inwardly about working outside in the cold.

Eventually, I recognized that I was really starting to suffer just raking some leaves! (Yes, it’s very similar to Ajahn Sumedho’s classic story…) The cold and damp was uncomfortable, but nothing to merit getting angry about. Seeing how miserable I was making myself, the heart let go. Raking leaves in the rain stopped being so awful. In fact, when I wasn’t wishing I were doing something else, it was even enjoyable.

Freedom from Identity

When I ordained, I also shaved my head, my beard, even my eyebrows (a cultural accretion in the Thai traditions) and donned simple white clothing and a white robe. I was given a new name in Pāli, Nyāniko. These changes themselves had a powerful effect: I almost didn’t recognize myself in the mirror!

Yet rather than feeling bereft or lost, I felt light, free, open. Removing the outer trappings of my identity, I felt a spaciousness and inner freedom. It was as if some inner slate had been wiped clean, including the social pressures and expectations of doing and accomplishing something, of being important or looking attractive…. I didn’t need to be anybody.

Over time, I watched how a new identity as ‘Anagarika Nyāniko’ began to form around the role, the clothing, and appearance. Witnessing how my sense of identity could dissolve and reform in relation to these externals was eye-opening. Who are we really when the self is so mutable?

Forming a new identity as a monastic is actually a key part of the training. The word for this is samaṇa sañña, which means the “perception of a renunciate.” The aim is to develop a clear sense of oneself as a renunciate, living devoted to the values of the path.

To support this, monastic rules outline an overall guide in how one lives, and this includes carrying oneself with a certain amount of care, presence, and dignity. So as an Anagarika, I also learned to follow a subset of the monks’ training (the Sekhiya rules) regarding general demeanor, including how one eats, how one walks and stands in public, etc.

Outside the monastery, I began to notice something interesting. I held myself differently, and felt held by the form. I no longer felt comfortable on autopilot. My habits of rushing about, subtly maneuvering to be first in line, occasionally oblivious to those around me, didn’t feel appropriate. The robes called me to a higher standard of behavior.

Being in public was no longer simply about me getting my list of errands complete. My presence represented something much more important – not just the monastery or the Buddhist tradition, but the potential for awakening and peace.

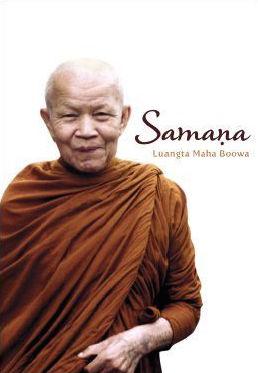

The life, rhythm, and flow of the monastery supported this. Everyone was committed to following the precepts, to non-harming. Instead of the constant messages of consumerism, I was surrounded by messages of presence, simplicity, devotion. Most rooms contained an image of the Buddha, and one bows three times (forehead to floor) when entering or exiting. Everything in the monastery is inviting one to slow down, to stop, to feel what’s happening.

This has a powerful effect at countering the messages of society that constantly tell us who we are, what we need, how to be happy. Instead, the renunciate life offered the joy of simplicity. Many mornings we would chant the reflection on the Four Requisites – clothing, food, shelter, and medicine – recollecting their purpose and our intention for awakening. This basic recognition supported an attitude of appreciation and contentment.

The Fruits of Renunciation

I don’t wish to romanticize the monastery. There were plenty of challenges and dreary moments just like anywhere else in life. In fact, they can actually be much harder in the monastery since most of the usual outlets for distraction are cut off. I resisted waking up so early to meditate many a morning! Yet the results of following the training were palpable. There is a dignity that comes from steady effort connected with purpose, and an inner strength that is born from not bending to the whims of the mind.

In those two and a half short years, I touched a sense of joy and contentment I had not known before. I learned that the heart can be profoundly at peace when it is resting in presence, connected to its own value. That studying desire, really working with craving, surrendering to a form, and following a training with love brings vigor and resilience to the heart. And, that there is beauty, grace, and fulfillment in letting go.

[Read the final post in this series here, about the decision to return to lay life.]